[ad_1]

The Parliament of Ghana is reviewing an on-lending agreement between the government of Ghana and a new Ghanaian state-owned development bank, DBG.

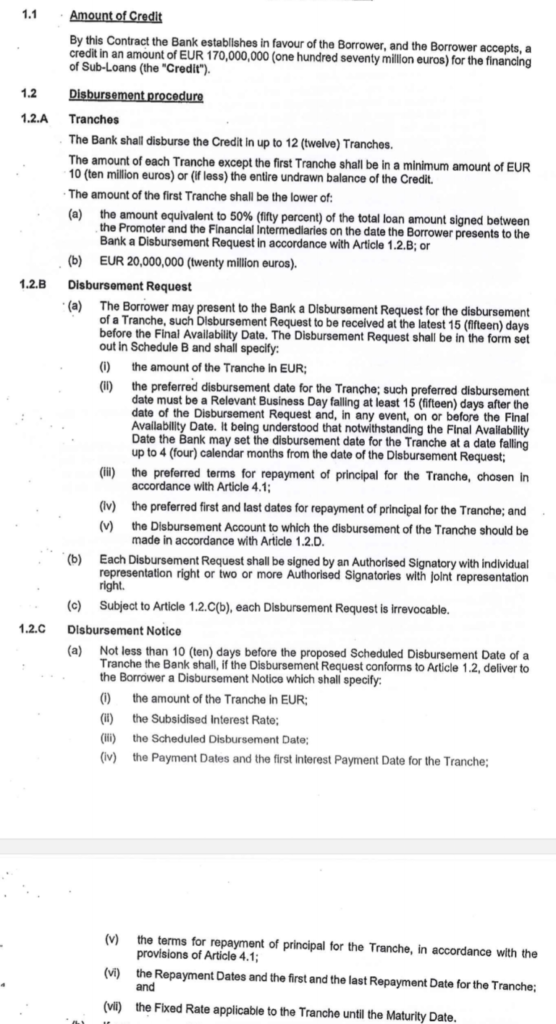

This agreement is a requirement for the European Investment Bank (EIB) to start releasing tranches of funds from a €170 million commitment to the DBG.

However, the decision to fund the DBG by key multilateral development banks such as the World Bank, Africa Development Bank (AfDB) and the European Investment Bank (EIB) was taken in 2019 when Ghana’s finances still had a shine. The kind of shine that billions of dollars of Eurobonds can confer.

After dragging its feet since 2020 when the EIB agreement was signed, the government of Ghana has finally dragged itself to Parliament to pursue ratification of the on-lending agreement between it (as the primary borrower) and the startup DBG (as the entity to disburse the funds).

But the world has changed enormously since 2019.

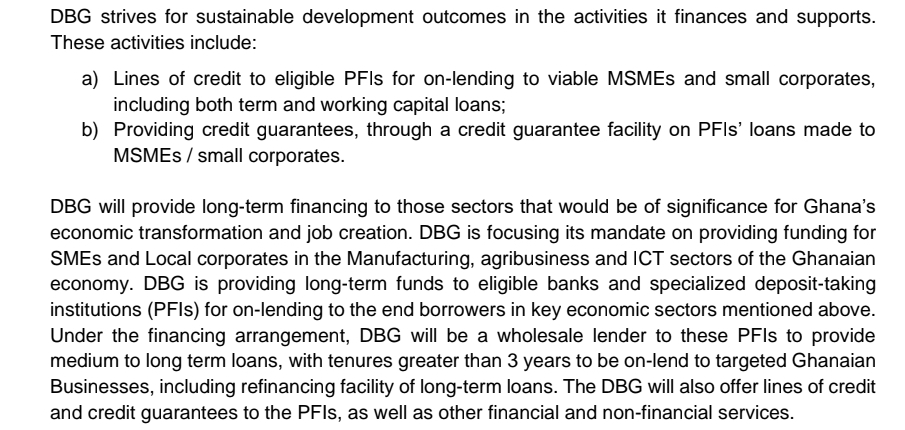

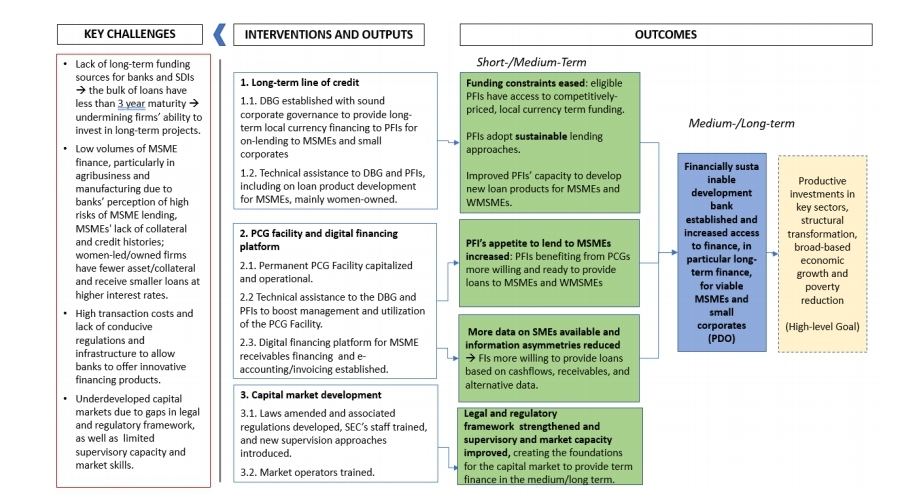

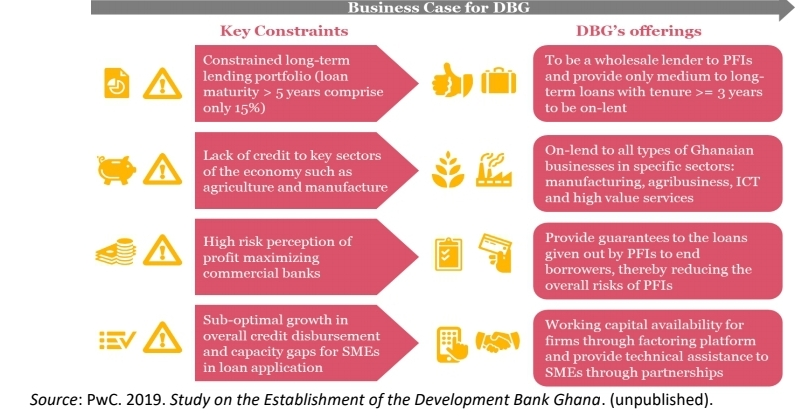

At a time when the country’s three existing development banks – Agricultural Development Bank, EXIM bank, and National Investment Bank – are widely considered to be poorly governed and heavily undercapitalised, and the finances of the country itself have crashed, the whole DBG wholesale on-lending model feels out of touch and out of place.

There are many challenges with the proposed DBG’s model that deserve very careful unpacking and in due course that will happen. But even without getting into the weeds, the very fact of expanding public debt in the name of development banking in a country struggling to restructure existing debt leaves a bad taste in the mouth.

We expect that Parliament – or at least the Opposition half of it, seeing as the government faction never performs any oversight – will subject this whole DBG program to serious scrutiny and insist on a proper national debate about the propriety of doing this at this specific time.

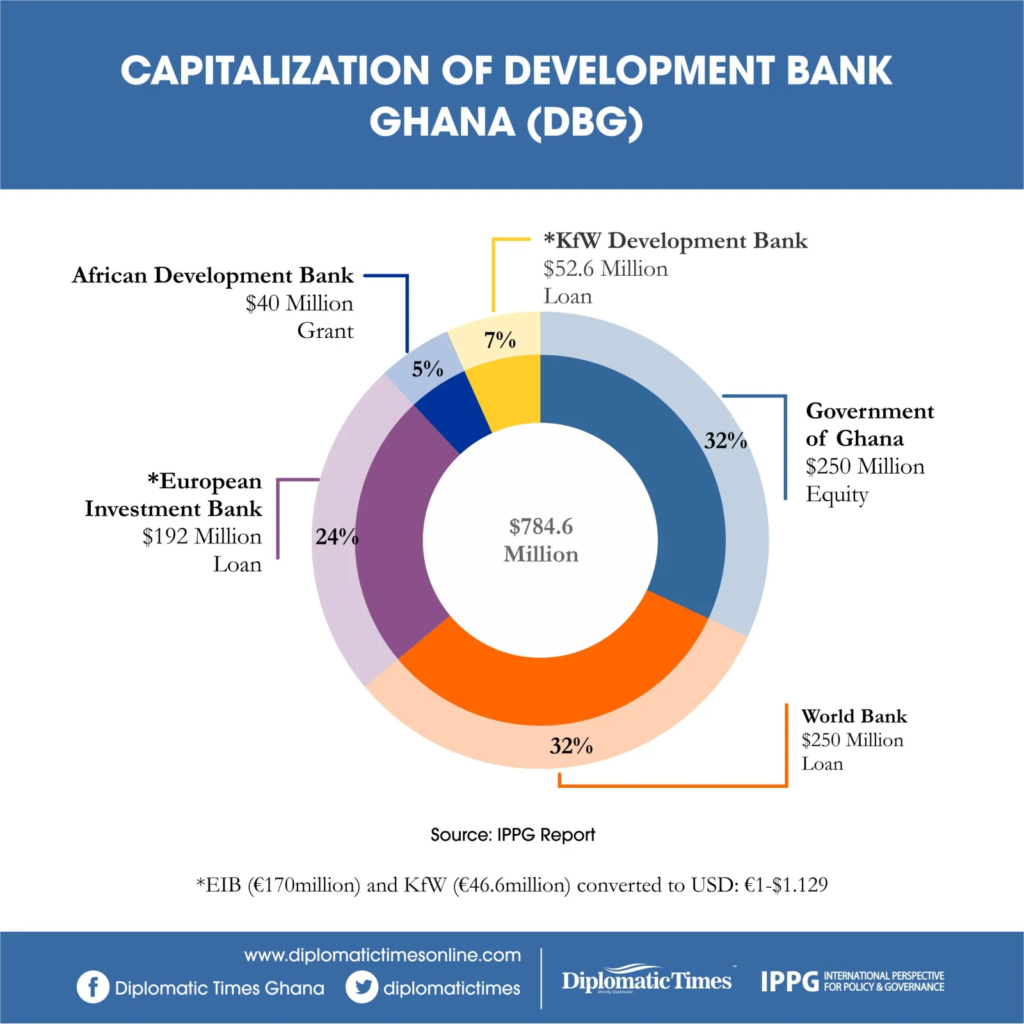

Bearing in mind that the World Bank is also supposed to release $250 million to the DBG at the same time as Ghana is pursuing concessional financing from the same quarters just to balance its budget. In total, the government intends to borrow nearly $800 million to execute the DBG strategy.

So far, the governance safeguards that were demanded by the multilateral development banks are merely assurances on paper. Some of the stipulations will be easy to follow. But those ones are the least important. For example, money from the EIB to the DBG cannot be on-lent to alcoholic companies, quarries or any mining projects.

Compliance in such circumstances is easily verifiable. Rules against nepotism, cronyism and disbursement to favourites are far harder to enforce. Yet, this is where state-owned banks in Ghana – development-focused or standard-commercial – typically falter. Two Ghanaian development banks collapsed in the 1990s after senior management facilitated cheque fraud by a corporate client to the tune of nearly 130 billion Cedis (old currency series). Less than 30 billion Cedis were eventually recovered.

Already, there are worrying signs that DBG operates according to the same opaque principles that all state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in Ghana do. It publishes little about its strategy, advertises available roles and consulting gigs half-heartedly, and gives a very limited account of how the tens of millions of GHS it says it has disbursed to SMEs were actually disbursed. Just another opaque Ghanaian SOE.

Whilst the qualifications of its initial bosses cannot be questioned, there are no indicators as yet of a corporate governance culture cut above the rest of the SOE landscape.

We hope that the EIB, AfDB and World Bank will not continue to enable public debt accumulation by Ghana with limited checks and balances and then when the country hits the rocks and is struggling to pay its creditors, everyone points the finger at someone else.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

[ad_2]

Source link